What’s the best job I ever had? The answer might seem obvious. From 1993 to 2006, I was a professional basketball player, a four-time NBA All-Star. I went to the playoffs multiple times with the Seattle SuperSonics and the New York Knicks and won a gold medal representing the United States in the 2000 Olympics. I earned millions doing what I loved.

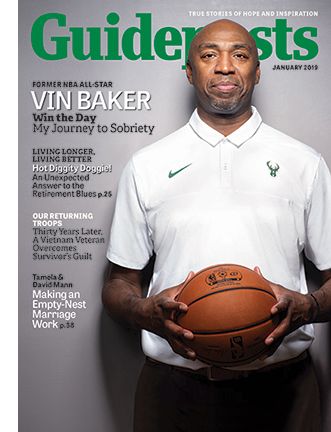

A no less worthy answer might be the jobs I held after my NBA career was behind me. For three years, I was a youth minister at Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem, one of New York City’s most vibrant places of worship. Two years ago, I joined the staff of the Milwaukee Bucks, the NBA team that had drafted me right out of college. I’m now an assistant coach.

Illustrious career, right?

issue of Guideposts magazine

Well, maybe. But you could make a case that the best job I ever had wasn’t related to basketball at all. That was the year I spent as a barista making lattes and macchiatos at a Starbucks.

I held that job from 2015 to 2016. At the time, I was a recovering alcoholic looking for a new direction in life. That NBA career? I was cut from the last team I played for in 2006, after it became clear to coaches that I couldn’t get a handle on my drinking. My struggle with alcohol began during my earliest days as a pro player and lasted until I hit rock bottom in 2011. By that point, I was broke and living at my parents’ house in Old Saybrook, Connecticut, drinking a gallon of cognac a day and waiting for the alcohol to kill me. How did I sink so low? How did serving gourmet coffee help me climb back? The answer to those questions is a God story, pure and simple.

I have no excuses for the addiction that wrecked my basketball career. I had a happy childhood in a stable home. My father worked as a mechanic and as a Baptist minister. My mom worked for a cosmetics company. My loving, faithful, no-nonsense parents didn’t even push me into basketball.

I was a standout at a small college—the University of Hartford—and was the Bucks’ first-round draft pick in 1993. I was 22 years old. Six feet, 11 inches. A center and power forward.

I was also plagued by anxiety. I’d grown up straitlaced and attached to my parents. I often went home for the weekend in college. The swagger of some athletes didn’t come naturally to me, especially under the glare of the NBA spotlight.

It didn’t take me long to discover the cure for my on-court nerves and off-court shyness.

It probably will not surprise you to learn there is a widespread party culture in the NBA. Many players are young, insecure and thrust into a world of sudden wealth, fame and public scrutiny. They deal with the pressure by drinking, smoking marijuana and throwing around money at clubs.

I was a faithful, churchgoing Christian through college. Those habits began to break down as my basketball career took off. Soon I was joining other guys on the team for postgame all-nighters, drinking and smoking weed at clubs.

The first time I drank hard with the guys, I made a wonderful discovery. My anxiety disappeared! I became the life of the party. I came to the conclusion that alcohol and marijuana were perfectly acceptable ways for a pro athlete to relieve the stress of a high-pressure job.

The path of my addiction was all too predictable. I went from partying occasionally after games to drinking almost every night. Somewhere along the way, I discovered I actually played better while buzzed (or so I thought). So I drank before games. Soon I was drinking every day, just to stave off the agony of hangovers and withdrawal. I was a hard-core alcoholic.

I bounced from team to team. Gained weight and got sent to rehab. Was suspended, then reinstated. Developed a gambling habit. Became addicted to anxiety pills. One Xanax-fueled night in Las Vegas, I blew $100,000 at blackjack.

I had children but didn’t get married. At best, I was an absentee father. When I was let go from my last team—the Minnesota Timberwolves in 2006—I had little savings. A disastrous restaurant venture left me essentially broke. My house was repossessed. I moved back to my parents’ house and waited to die.

So where does Starbucks come in? I entered rehab for the fifth time in 2011. My father drove me. There was no reason for him to hope. Except this time I had begged God for help.

And God answered. I found a commitment to sobriety I’d never experienced before. I returned to my childhood church—my dad was still a pastor there—and threw myself into Bible studies and volunteer work.

There was just one problem. I needed income. And now that I was reaching out to my children and trying to repair the relationships I had destroyed, my financial obligations were growing.

Out of inspiration, I called Howard Schultz, the founder and CEO of Starbucks. Howard had owned the Seattle SuperSonics when I played for them. He was someone I admired who could give me advice about my future.

Howard gave me more than advice. First he set me up with Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem. He was friends with Dr. Calvin Butts, the pastor. I worked as a youth minister while attending Union Theological Seminary. I had thoughts of going into ministry, though I wasn’t sure.

After returning to Old Saybrook as a licensed minister and marrying the mother of my children, I once again needed income. And once again Howard Schultz came through. I was mystified by his offer: train to become a Starbucks manager. My previous attempt at business—the restaurant I opened—was a spectacular bust. I’d never worked behind a counter in my life. And I knew nothing about coffee. But I needed a job, so I said yes.

It was the best decision I ever made.

Here’s the thing about the NBA: It’s not real life. It’s hard work on the court. But it’s a collective fantasy. A place for fans, for entire cities, to project their aspirations. The wealth is mind-blowing. The schedule is grueling. Players travel all the time. It’s hotel rooms and luxury lockers and pulsing arenas and media glare. For young players, it’s easy to confuse the fantasy with reality.

Working retail? That’s reality. Especially when you work your way from barista through all the jobs you’ll eventually manage—if you make it.

I was given an easy shift at first—8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m., avoiding the morning and evening rush. Still, the work exhausted me. I had no idea there are so many variations on coffee. I had to learn them all. How to make them and customize them. How to work the register and keep the store supplied and clean.

Soon I was waking up earlier than I ever had in my life to open the store. Getting behind the drive-through microphone was like strapping in for a road race. Orders came fast. Every one was different.

I made a lot of mistakes. Once, an impossibly complex order came in. I was reduced to punching random buttons on the register and hoping for the best. When the customer drove up—it was my training supervisor!

“Gotcha!” she shouted. I was relieved to see her smiling. Because I had messed up that order, start to finish.

Working at Starbucks was the hardest job I ever did. I loved it. All I had to do was win the day.

I loved waking up early—and sober—and heading to work like everyone else in the world. I loved being part of a team that was working to serve other people.

“Look, I know I’m supposed to be your boss,” I told employees when I took on more management duties. “But I realize you know more about this place than I do. Let’s just help each other out and work together.”

Help each other out. Work together.

On my best days in the NBA, life felt like that. But I didn’t have many best days in the NBA. Mostly I was so lost in my own insecurity, so weighed down by vanity and ambition, I sought release in all the wrong places.

Howard Schultz is a wise man. Working at Starbucks showed me that a life of service—the life Jesus wants us to live—can happen anywhere. In the NBA, I’d been the fantasy Vin Baker, the basketball star pouring alcohol into an inner void. At Starbucks I was just Vin Baker. And I loved it. I needed it.

Eventually basketball came calling again, and John Horst and Mike Budenholzer, the general manager and head coach of the Milwaukee Bucks, gave me an opportunity to be on the staff of my first NBA team. It was a God-given chance to take what I had learned at Starbucks and in recovery and offer it to young players in desperate need of a veteran’s hard-won wisdom.

I’ve been sober for seven years now. I thank God for every sober day I live. I thank him for the many opportunities I’ve been given—especially the opportunity to live again after so much self-destruction. To live at last in the realness of God.

For more inspiring stories, subscribe to Guideposts magazine.