I should have known there was something wrong with me when I sustained my fourth concussion. It was the 2007 season, my fourth year in the NFL as a tight end for the Indianapolis Colts. We were the defending Super Bowl champs. In a game against the Denver Broncos, I was blocking for our running back. A Broncos defensive back leaped over me, trying to get to the ball carrier. His foot clipped the back of my helmet.

I only know what happened next because I watched it on film. I crumpled to the ground. Ten seconds later, I jumped up and sprinted to the sidelines, where I talked with my teammates and a doctor, who pulled me from the game. I had no memory of any of it.

I’d never experienced amnesia. Still, when I told my wife, Karyn, I didn’t make a big deal of it. I’d had concussions before. I’d always bounced back.

I needed to bounce back. My contract was up at the end of the season, and I wanted to sign a long-term deal. It would mean financial security for Karyn and me and the family we hoped to start.

My list of injuries went back to junior year of high school: broken pelvis, ankle and foot; fractured ribs and vertebrae; torn abs. To borrow an expression from Karyn’s sport—she was a captain of the women’s golf team at the University of Minnesota, where we met—getting banged up is par for the course in football.

Four weeks later, I passed the Colts’ post-concussion protocol and was cleared to play. During the off-season, I signed a three-year contract with the Cincinnati Bengals.

Leaving my friends in Indianapolis was hard. I also left my mentor in the career I dreamed of having after football: music. I’m a big guy—six foot six and 250 pounds—and I have a big voice. My dad is a Methodist minister. I sang in his church as a boy. In high school I was in more choirs than sports teams. In college I sang at churches with the Fellowship of Christian Athletes. I did the same in Indianapolis.

My rookie season I spoke at a youth event. A woman in a Colts jersey ran up afterward and asked for my autograph. She was none other than Sandi Patty, a huge Christian music star. I wanted her autograph.

Sandi took me under her wing. In December 2007 I joined her onstage at the Indianapolis Festival of Lights. Singing with a Christian music legend in front of more than 100,000 people while wearing my Super Bowl ring was a dream come true, something only God could have orchestrated.

I should have known there was something wrong in spring 2008, when I had trouble learning the Bengals playbook. None of it stuck in my brain, which was weird, because I’d always had a phenomenal memory. I didn’t connect it to my concussions, though. Concussions weren’t in the news back then. Two sets of doctors—on the Colts and the Bengals—had cleared me to play.

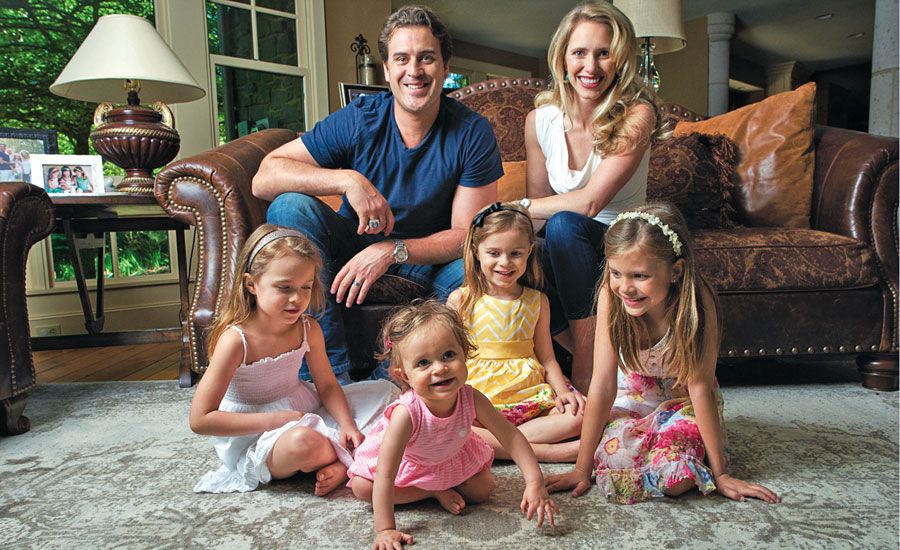

The 2008 season wasn’t a good one. I broke my sternum and tore my plantar fascia. But I went into the 2009 training camp in the best shape of my life. I had extra motivation: Karyn and I had had our first child, our daughter Elleora.

I should have known there was something wrong when I was knocked out on August 5, 2009. It was the first week of training camp, a routine blocking drill. I was supposed to handle the outside linebacker. That’s all I remember. The rest I pieced together from my teammates and from film (HBO’s Hard Knocks covered our camp).

The linebacker’s helmet came up under my face mask and hit me on the chin. I was out cold. Coaches, trainers and camera crews ran over. I came to before the ambulance got there. Hard Knocks showed my teammates praying for me. Paramedics rushed me to the ER. Doctors cut off my uniform and pads. Little did I realize that I would never wear a uniform in competition again.

I went through a bunch of tests. I had practically every symptom of post-concussion syndrome. Headaches, dizziness, sleeplessness, night sweats, sensitivity to light, loss of balance, fatigue, nausea, forgetfulness, difficulty concentrating, irritability.

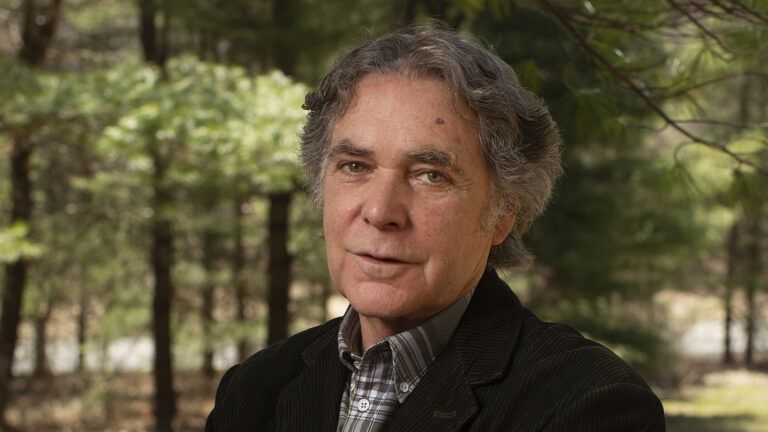

I should have known there was something wrong when those symptoms didn’t go away. When every doctor I saw—including a neurosurgeon and concussion expert, Dr. Robert Cantu— told me I should never play football again. The Bengals cut me in November.

READ MORE: NFL PLAYER’S BATTLE WITH CROHN’S

Still, I made one last attempt to resurrect my NFL career. In April 2010, I finally passed the return-to-play protocol and tried out for the New England Patriots. I killed the workout but the Patriots didn’t sign me. Too big a risk with my concussion history, they decided. The end had come for me as a football player.

The question was: Who was I now? I thought I’d find the answer in music. We moved to Nashville in May. A few months later we found out Karyn was pregnant with twins. I’d felt so unsettled about the future, yet here was God with a double blessing. A reminder of what my parents had always taught me—to trust my future, my family, everything, to the Lord.

The birth of our twins, Katriel and Amy Joan, confirmed that trust. So did meeting Jim Brickman, the great adult-contemporary musician. Jim hired me for his Christmas 2011 tour.

We moved home to Minnesota that summer. Karyn would have help with the girls while I was on tour, and the girls would be close to their grandparents.

One night we went to see our good friends Matt and Kim Anderle. Matt was my teammate in college. He mentioned something about their wedding some years back. Karyn wanted to hear more. So Matt and Kim started telling stories.

With each story, I got angrier, wondering why I hadn’t been asked to the wedding. My NFL schedule had been crazy, but I would’ve made time. “Why didn’t you invite me?” I demanded.

At first they all thought I was joking. Then Kim got out their wedding album. “You’re right there, Ben,” she said.

“You weren’t just a groomsman,” Matt said. “You sang for us. Don’t you remember?”

READ MORE: NFL STAR’S INSPIRING NEW GAME PLAN

The photos didn’t trigger the faintest recollection. I had absolutely no memory of their wedding. They all stared at me as if I was somehow fragile and broken.

That was the first time it hit Karyn and me that something was terribly wrong. I hadn’t really shared my memory problems with her. I didn’t want to burden her. Now it was clear I wasn’t just forgetful. Memories had been erased. My brain had changed.

On the Jim Brickman tour I couldn’t remember lyrics, not even to old Christmas songs. So I taped the words to the stage. Still, I loved being on tour. Concert night felt like game day. It gave me the same rush.

Maybe that’s why I sank into a depression when the tour ended. Karyn, the girls and I had settled into our dream home. I should have been happy.

Instead, most mornings I couldn’t get out of bed. I didn’t have a job to go to anymore. Not in football. Not in music. I’d been reading about the effects of concussions on former NFL players. Some were legends, others were journeymen. They all suffered alarming memory problems and behavior changes. Some died young and tragically, many by their own hand. Is that going to be me? I thought.

Karyn would ask quietly, “Are you going to come down? The girls want you.”

One day I forced myself downstairs. We were potty-training Elleora. Karyn asked me to take her to the bathroom. I put Elleora on the toilet and sat on the edge of the bathtub. “I’m done, Daddy,” she announced.

“Did you go potty?” I asked.

“I don’t need to.”

“You need to try,” I said.

She frowned. “I can’t.”

READ MORE: FAITH, LOVE AND MARRIAGE AFTER A BRAIN INJURY

I stood, looming over her. “You are going to sit there until you go.” My voice rose. “Do you understand me?!” Elleora burst into tears and I caught a glimpse of myself in the mirror. What have I become? Someone who scared his daughter. Someone who scared himself.

Karyn comforted Elleora. I went into my study, closed the door and fell to my knees. I’ve let this brain injury get the best of me, Lord. I surrender. I give it over to you. The best and the worst.

Something hit me at that moment. The Lord freed me from the anger and self-pity that were suffocating me. And he opened my eyes to the people, the blessings, around me. The world as it was in this moment.

After that, I got up early every day for time with God. One morning I was in my study when the door creaked open. “Daddy, can I come in?”

“Of course, Elleora.” She was still in her pajamas. I pulled her up onto my lap.

She snuggled close. “What are you doing?”

“Reading my Bible.”

“Will you read to me too?” “I sure will.” I wrapped my arms around Elleora and read.

“Can we do this again tomorrow, Daddy?”

It has become our morning ritual, one that anchors my day.

READ MORE: TONY DUNGY—WHEN MENTORS MOLD THE MAN

I poured my feelings—my love for my wife and daughters, my fear that I would not remember them one day—into a song I wrote and released in 2014. “You Will Always Be My Girls” has had more than 1.25 million views on YouTube. I think people respond to the truth in it.

The truth I should have known but tried to avoid for so long: Everything that I am, the person I’ve been, the man I hope to be, all comes down to my ability to remember. That is why I speak out about brain injury. Why I get up every morning determined to make the day count. Why I’ve been doing a new kind of training, for cognitive fitness.

Last summer I took part in a program that was as hard as any NFL training camp. At the start, I tested in the seventeenth and twelfth percentiles for recent and long-term memory. Very poor. I did 120 hours of work with a brain trainer. By the end, my scores jumped to the seventy-eighth and ninety-eighth percentiles. It was like moving from the bottom of the football depth chart all the way to the top.

Isn’t it awesome what the Lord can do when you let him make the best of you?

Did you enjoy this story? Subscribe to Guideposts magazine.

Sports and Brain Injuries

Recent news stories and a 2015 Hollywood film, Concussion, have brought to light the dangers of brain injuries in contact sports, especially football. In organized high school sports, football accounts for more than 60 percent of concussions. The NFL reported 271 concussions in 2015, and nearly 40 percent of retired NFL players have described symptoms of traumatic brain injury. After football, hockey has the highest concussion rate. College basketball has also seen steady increases in the injury.

Repeated concussions have been linked to memory loss, problems focusing, dementia, fatal blood clots and chronic traumatic encephalopathy, a degenerative brain disease. The American Academy of Neurology concluded in 2014 that wearing a helmet reduced the risk of traumatic brain injury by only 20 percent.

With milder concussions, symptoms like dizziness, blurred vision and headaches can last up to a week. With severe injuries, when consciousness is lost, recovery can require limiting activity for up to a year. The good news is that, as Ben Utecht describes, programs are being developed to treat brain injuries, and sports programs are addressing the issue.—Tyler Burdick, Editorial Intern