Eight months after setting out on the 2,190-mile Appalachian Trail, I was a mere 120 miles from finishing.

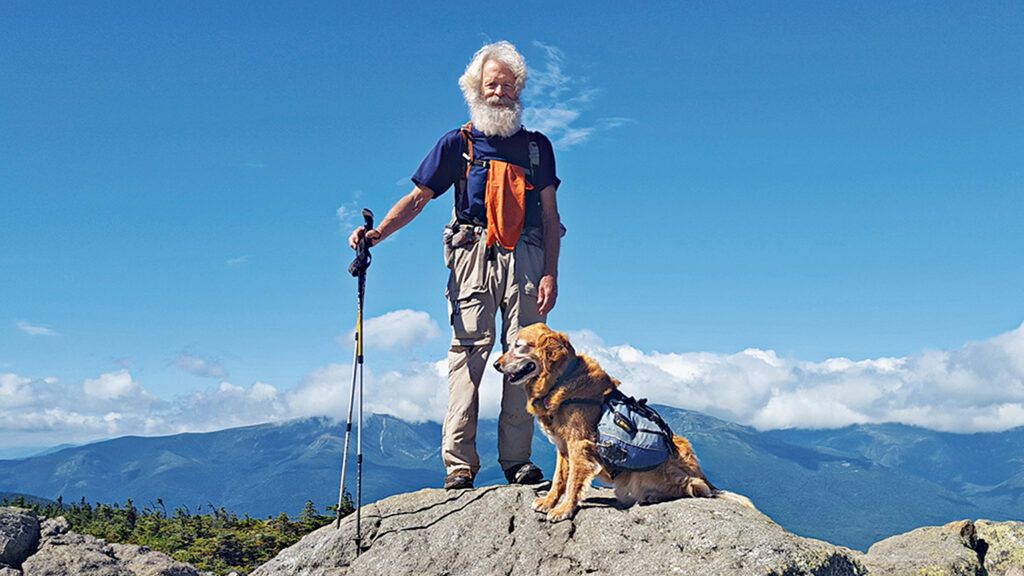

It was October. Ahead lay Maine’s One Hundred Mile Wilderness, one of the most remote and unforgiving stretches of country in the eastern United States. I was 75 years old, and I was exhausted, mentally and physically. I’d lost 30 pounds since starting the trail at Springer Mountain, Georgia. My white hair and beard were long and unkempt.

I was in the hospital. Tendons in both arms were torn after frequent falls. My right shoulder was swollen, hot and useless.

Did I plan to quit? Absolutely not.

All my life, I’d wanted to hike the Appalachian Trail—the AT, as we hikers call it. I’d postponed that dream through decades of work and family life. The call to thru-hike the trail—hike it from one end to the other in a single year—came from some deep part of me I still didn’t fully understand. Who or what was calling me? I had to get back out there to find out.

I’d first encountered the Appalachian Trail in the White Mountains of New Hampshire during summer camp when I was 12. The AT passes through the heart of the Whites, traversing a spine of bare rock called Franconia Ridge. Our backpacking route had followed the trail across the ridge, which is often buffeted by strong winds. Hiking that ridge, blown by the wind, surrounded by the peaks of the Presidential Range, I’d felt a strange exhilaration.

Two years later, I suggested to a school friend that we hike the entire trail. Life went on, and the hike never happened. I went to college, got married, became a father and opened a law practice in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, where my wife, Bonnie, had grown up. We had five kids, three boys and two girls.

Though the AT was 50 miles from our house, I never set foot on it. I did some camping with the kids but otherwise did exactly what the world expected of a responsible husband, lawyer and father of five. That did not include spending eight months walking in the woods.

There’s a reason I was so responsible. My parents were alcoholics. They fought a lot when I was a kid. Life was unpredictable. My brother was the rebel. I was the good son.

I did all I could to make sure my own kids’ upbringing was steady, secure. Bonnie and I were active at our local parish and in prayer groups. Work, family and church were my top priorities.

The kids grew up and went off to college. Bonnie and I were in our sixties. One day, nearing my sixty-fifth birthday, a thought jumped into my head: Wouldn’t it be neat to celebrate that birthday on top of Katahdin?

Mount Katahdin—Penobscot Indian for “Chief Mountain”—is the northern terminus of the AT. Summiting this mound of rocks, just 13 feet shy of a mile high, is the crowning achievement of a northbound thru-hiker.

I hadn’t thought of the trail in years, yet suddenly I was hooked. I announced to Bonnie that I planned to hike the Appalachian Trail. I didn’t ask. Just announced.

“Mm-hmm,” she said, looking at me as if she would have appreciated some input. But the desire to hike that trail welled up from some deep part of me, where the memories of that boyhood hike on Franconia Ridge were stored. There was something wild out there, more true and life-giving than the routines of everyday life.

True to form, I didn’t walk out the door that minute. I wound down my law cases and hiked more than 400 miles in Vermont and Pennsylvania to prepare myself and my golden retriever, Theo, who would accompany me on the trail.

It took me 10 years to get ready.

On Valentine’s Day, 2016, my family gathered to bid me farewell. I gave Bonnie a ring with three precious stones, representing our love for each another. On February 18, I kissed her goodbye and headed for Springer Mountain. Theo and I were on our way. They say a thru-hiker takes five million steps on the AT. Theo might take twice that many.

It was winter. An experienced thru-hiker cautioned against starting the trail so early. A native New Englander, I wasn’t bothered by cold and snow. I had a tent with room for Theo and me, a sleeping bag, cooking gear, rainwear, emergency supplies and warm clothing. Down booties at night were a real plus.

We passed through the Great Smoky Mountains in heavy snow, the Virginia highlands in sun, the Shenandoah Ridge in rain, then West Virginia and Maryland. We settled into a comfortable rhythm of walking all day, pitching camp (while Theo rolled in the dirt or leaves to rub off the feel of his saddle bags), filtering water, preparing food and sitting together peaceably in the gloaming. I reveled in the endless woods, the majestic views and the silence.

Most of all, I loved not knowing where I’d sleep or what was over the hill. I was free from the routines of society. AT thru-hikers traditionally adopt trail names. Mine was Sojo, for Sojourner. I was on a journey, led by God.

After 500 miles, I switched to summer gear. A few miles later, I realized my low-cut boots were causing blisters between my toes. I developed plantar fasciitis. By the time I reached Pennsylvania, known as “Rocksylvania,” things were rough. Theo was managing fine. My feet, however, were killing me.

In Port Clinton, at the foot of a steep descent, I took a break. Bonnie met me. She looked at me, thin and exhausted, and said, “You need to come home.” I knew she was right.

At home, Bonnie was amazed how I downed a full blender of milkshake in one gulp. She shopped for the best health foods for me to take on the trail. My doctor wanted me to stop for fear of dehydration, but I told him I’d be fine. I saw a podiatrist, who showed me how to protect my toes with toe spacers and moleskin pads. Using the spacers and pads and wrapping my feet in duct tape, I headed back to the trail after a three-day break. My feet gradually healed.

My shoulders didn’t. I fell more than 30 times on the rocky trail, bracing myself and my 30-pound pack every time I landed. For a long time, I ignored the pain. I made it through the mid-Atlantic states and headed into New England at the height of summer. By August, I was back in the White Mountains, back on Franconia Ridge, back in the rocky, windswept terrain that had first inspired my love of the AT. The strong winds and kaleidoscopic fanfare of clouds and sunbeams made me feel as if God himself were welcoming me.

It took me days to get through the Whites. After some of the trail’s most difficult stretches, including a mile of huge boulders, some requiring that I remove my pack and crawl underneath, I arrived in Monson, Maine, at the start of the One Hundred Mile Wilderness. I could ignore my shoulders no longer. I feared my right shoulder was infected.

A doctor drew 45 ccs of cloudy fluid out of my shoulder and put me in the hospital for four days of IV antibiotics. He wanted to operate.

I knew that the trail up Katahdin closes by mid-to-late October. I would never make it if I had surgery. I told the doctor I wanted to hike.

Summiting Katahdin in October can be hazardous. I had to break up the last section of the trail and tackle the mountain while the weather held. I took a shuttle van to the base of Katahdin. Theo and I got up at 3 a.m., summited at noon and made it back for a shuttle ride back to Monson that same day.

Then we set off through the One Hundred Mile Wilderness, the last leg of the trail. It took us 10 days. I was numb in body and spirit. A thunderstorm turned to snow for seven days. I walked through rivers in full gear. My fingers and toes were frozen. The whole time, I’d picture Bonnie and the kids and chant in rhythm with my footsteps: “Their… love…will…see…me…through.”

On October 27 at 1:45 p.m., I took my five millionth step, exiting the trail. My thru-hike was over.

There was no elation. No celebration. Katahdin was under five inches of snow. I’d made the right decision to summit it earlier.

Bonnie flew to Bangor, Maine, and rented a car to meet me. It was wonderful to see her, but we were both too dazed for excitement.

Now I was done. And I was different. But how?

Back home, I felt alienated from everyday life. The trail was like a river running through my mind. Memories flowed past of the trees, the streams, the sky, the clouds, the wind and the peaks.

What had I found on the trail that had been calling to me for so long?

There was my love at the end for Bonnie and the kids. But that love, I knew, was embedded in a larger love. For so long my love for my family, my sense of responsibility, came before hiking the AT. I never questioned that decision.

But when at last I said yes to the trail’s call, I discovered why it was so powerful. It wasn’t just woods and water and rocks and sky that I found. I found God himself. He accompanied me every step. He showed me sides of himself I’d never experienced. On the AT, I found a wild God, the God of all creation, the God of love, companionship, protection and support. The God who saw me through a difficult childhood and gave me answers to the questions I didn’t even know to ask. God’s love never ends. For a thru-hiker, neither does the AT.

For more inspiring stories, subscribe to Guideposts magazine.