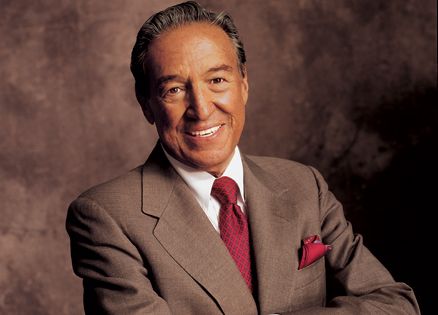

When I interviewed Mike Wallace about his battle with depression (“My Darkest Hour,” January 2002, Guideposts), I didn’t realize I’d also be talking with him about another painful experience—the death of his 19-year-old son Peter in 1962. When I first brought it up he was quiet for a moment, pensive.

As a father of two sons myself, I knew how difficult this would be for him. I worried I had overstepped. But then in his matter-of-fact way, he said, “Okay.” This is when I learned how his son’s death came to change Mike Wallace’s life.

“I’ll always remember that late summer in 1962, leaning against a jet’s window, staring down at the Mediterranean. My 19-year-old son had disappeared and I was on my way to find him.”

The strapping Yale student was Mike’s eldest. “The last we heard was that he was on a jaunt in Greece.” Mike smiled in memory. “If there was one place Peter loved to be, it was that ancient Mediterranean country. Even as a youngster, he had explored its history. I could still see him as a little boy proud in a bedsheet toga, brandishing a wooden sword from behind a garbage-can-lid shield.

“Peter had written about going to a little town called Kamari on Santorini Island in the Aegean Sea. Suddenly his letters stopped,” Mike said. “Despite our attempts to locate him, it was as if he had disappeared from the face of the earth.”

Fraught with anxiety, Mike cancelled a global news trip and caught the next plane for Athens. All the way he tried to console himself with “what ifs?” Maybe he had found a girl, Mike thought, and the two had taken off. He was ready for anything.

From the Athens airport he raced to the American Embassy. Together with an understanding consul he flew to Kamari. It was a beautiful seaside town with ancient ruins and black-sand beaches.

“Just the kind of place Peter loved,” Mike said. “Many of the local folks we talked to remembered the tall, brown-eyed man.

“They pointed up a mountain that loomed over the sea,” he continued. “They said a monastery was on top of it and Peter had gone up alone to see it.”

Mike said he could understand, as he squinted up in the dazzling sun. Just like Peter, he thought.

But he had never returned. Searchers found no leads. Those in the monastery had not seen him. “My son seemed to have vanished into thin air,” Mike said.

There was only one thing to do.

The consul and he got some donkeys, a necessity for the precipitous stony mountain climb, unless one was a young athlete like Peter. They slowly ascended, the Mediterranean sun hot on their backs, while their dun-colored beasts picked their way up the dusty ochre path.

As they climbed higher, Mike began to sense Peter’s presence; he had trod this very path.

“His very curiosity in visiting the monastery reflected his spiritual bent,” said Mike. “I remember him talking about the Greek philosophers’ search for meaning in life. One day he said to me, ‘Dad, you know that famous line in Shakespeare’s Hamlet, To thine own self be true? Shakespeare took that from Socrates’ Know Thyself.’”

That was Peter, forever seeking, always looking for a deeper meaning in everything.

“Was it tears or sweat stinging my eyes as we plodded higher?” Mike continued. The hot, dry air seemed too thin and a breeze brought a briny scent from the sea.

“The view took my breath away. Thrown out before us was a scene I could have never imagined—a vast panorama of the Aegean stretching across the horizon. Dark islands punctuated its cerulean surface. I took a deep breath and knew Peter would have stopped here to feast on this wonderful vision.”

Mike turned to the consul. “Let’s take a break for a moment,” he said. They dismounted and stepped to the overlook. “Neither of us said anything as we drank in the magnificent view.

“And then I happened to look down at the earth before my feet. It had been disturbed, as if it had given way under…someone? My heart pounded. I didn’t want to look down that mountainside. But I had to.

“Some five hundred feet below lay the crumpled body of my son. Even from that height I knew it was Peter. He was wearing the bright madras shorts we had bought together from Rogers Peet men’s store in Manhattan.”

Mike’s voice choked. “I fell to my knees in anguish. The rest of the nightmare was a blur.” All Mike could remember was being back on the mainland for the formalities, driving behind the pickup carrying the rough wooden box holding his son’s body in the glare of the headlights.

“We buried Peter at the spot where we found him, where he would have loved to be, looking out over the Aegean,” said Mike softly. “Some of the townsfolk joined our little family as we left him to God. Through my agony and tears it was almost as if he was saying, It’s all right, Dad. It’s all right.”

But that was not the end of Peter.

Before Peter’s death, Mike had a varied career in broadcasting, including heading a tough-minded, controversial program called Night Beat in which he had begun to develop an interview style.

But in 1962 he was mostly reading news on television. “Rip and read, as we called it,” said Mike, a term dating back to when reporters snatched the news off the teletype to read over the air.

But Peter’s death changed him.

“I felt strongly led to do something more significant, more meaningful, as if I was again hearing, To thine own self be true. Peter wanted to follow in my footsteps. But so far I didn’t think he’d be proud of the ones I had been leaving,” Mike said.

That’s when Mike quit everything and decided to take a year off and reevaluate his life. He wouldn’t go back to work until he found something Peter and he would be proud of.

Mike had been making a hundred and twenty-five thousand dollars a year when a call came offering him the news anchor at KTLA in California. It was tempting, but then he heard from Richard Salant, then President of CBS News. Mike had interviewed him on Night Beat.

“Mike,” Salant urged, “I know you’ve been making more money, but if you’re really serious about doing something special, come on over here. The salary is forty thousand a year, a lot less, I know, than what you’ve been making, but it may be the beginning of something for you.”

“It sounded right,” said Mike.

And so he worked as a reporter, each night praying the Shema: Here O Israel, the Lord our God, the Lord is One. “Undergirding my faith. I was on the right path,” said Mike.

“I didn’t know what I was being groomed for,” he said. “But five years later in 1968 Richard Alant finally gave producer Don Hewitt the okay to start 60 Minutes, which is where I have been ever since.

“Sometime later, I returned to Peter’s grave to kind of tell him what I had been doing, though I’m sure he knew it all along.” Again he rode a donkey up that very steep, stony climb to where the magnificent Aegean spread out before him. When he reached Peter’s grave he was stunned.

The Kamari townsfolk, who knew how much Peter had loved their homeland, had adopted him as one of their own. They had erected a simple tombstone and enclosed his grave with a wrought-iron fence entwined with graceful metallic leaves.

Struggling with emotion, Mike looked out on the sea his son had loved so well and felt his presence again. “Thank you, Peter,” he whispered.

Download your FREE ebook, True Inspirational Stories: 9 Real Life Stories of Hope & Faith