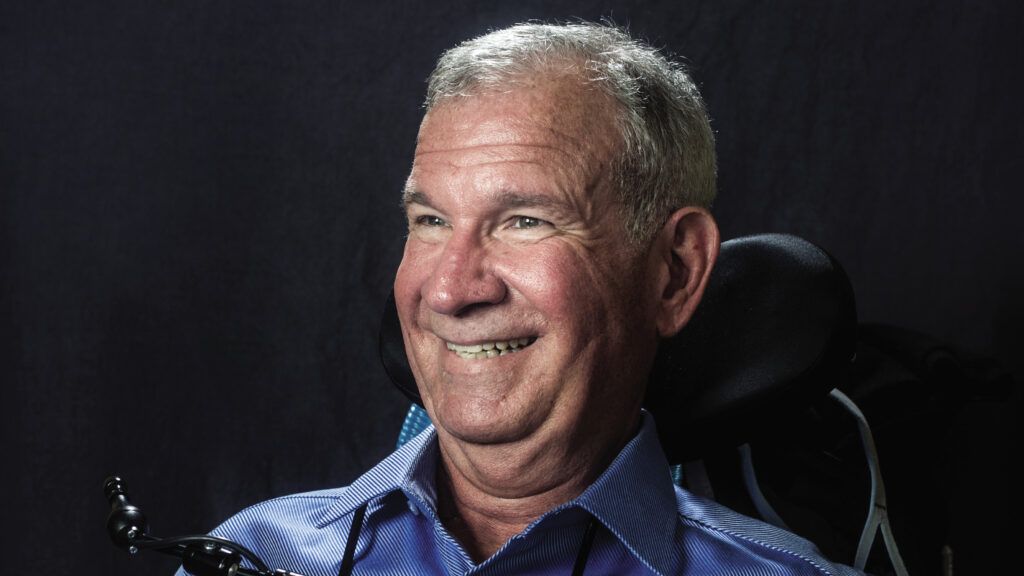

John R. Paine had it all. He was a respected businessman, devout Christian and dedicated father.

Then he received a diagnosis that changed everything. He had ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, and was told he wouldn’t live long.

Seventeen years later, Paine has long outlived the doctor’s prognosis. He uses a wheelchair to move and a ventilator to breathe, but has found deep joy in his relationship with God. Paine shares his story of pain and spiritual formation in his new book The Luckiest Man.

In this excerpt from his book The Luckiest Man, Paine opens up about how ALS opened his eyes to the beauty of depending on God.

Saying Good-Bye

I’d said goodbye to so many things: climbing stairs, swimming, scratching any given itch. I’d hired a full-time driver who doubled as a part-time caretaker. I’d maintained the rhythm of my evenings, perhaps my favorite part of any day, though I knew it was only a matter of time before that changed too.

Margaret has always been an early-to-bed kind of girl, and in those days, she’d settle into bed sometime around nine o’clock each evening. I’d make my way to my favorite deep-cushioned chair by the bed, often reading until close to eleven. Satisfied, I’d settle into bed and fall asleep, spent. It was a good arrangement, one that worked for me. I was growing weaker, though, and with each passing night, I found myself struggling to maintain the rhythm. My arms now dead, Margaret would open my book, set it in my lap, and place my hands on either side. With my right thumb and forefinger, I’d turn the pages with great care, sliding the edge under the fingers of my resting left hand. It was a tedious process and grew more tedious by the day. When I was finished, I’d stand, shuffle to the bed where Margaret had pulled the covers back, and with a series of arm slings and knee raises, I’d pull the covers over my chest before falling to sleep. It was unconventional, but isn’t so much about adapting to death?

It was a night like any other, though I should have seen it coming. The routine had been the same—the chair, the book, the pulled-back covers. Having had my fill of reading, I stood, allowed the book to fall from my lap to the floor. I dragged to the bed, then stretched myself under the covers. I tried to sling my arms up using my knees, tried to throw the covers over my chest; I couldn’t. It was no use; I couldn’t cover myself.

I turned to look at Margaret, already asleep, and there was no way I would wake that kind of resting peace. Pity set in—self-pity is a difficult battle for the ALS patient—as I realized there was no feasible way to solve this problem. In that pity, I was overcome by emotion. Tomorrow night, would I have to turn in with Margaret? Would I have to let her tuck me in and turn off the lights? Would I stare up at the dark ceiling, unable to move until I was able to fall asleep hours later? Did I have to say goodbye to my favorite part of the day?

I rolled to my side and climbed out of bed, arms dangling. I shuffled back to the chair I’d just left and sat in fresh awareness of my newest loss. Why tonight? Why ever, really?

I felt the sadness and resentment and depression creeping in, knew that this kind of self-pity made life so much darker, so I turned to prayer. I waited for an answer, a sense, anything. I heard nothing. I waited, started praying again, and that’s when a movie started playing in my mind’s eye. It was the video of my life. I was a young boy in Tyler, running from home, pushing past the boundaries my parents had set. I was a college student in love, but I was spending more time away from Margaret, more time pursuing academic achievement. I was married, working for Mr. Hill, and asserting my independence more and more. I was a successful builder, an entrepreneur, a self-made man. I was sitting in the doctor’s office, the recipient of a terminal diagnosis, and even in my success, I felt so alone. Where were my parents? Where was Mr. Hill? Where was Margaret, really? They were a part of my life, sure, but were they in it? Were we connected in intimacy, connected in such a way that would help me carry the load? Hadn’t all my assertions of independence been nothing more than acts of isolation?

That’s when I felt the words, flooding.

I created you for dependence on me and others. Your pursuit of independence pushed all of us to arm’s length. Say goodbye to independence. Really.

Conviction is a difficult thing. First, He’d convicted me of my understanding of His love, then of ways I sought validation. Now He was showing me that dependence was not weakness, so long as I was dependent on the right things. And just as it had in those other moments, this new moment of conviction brought a sorrow with it. This false independence, all this striving to prove my self-sufficiency—what was it worth? How had I missed this truth, that God created us for proper dependence? I knew it at once—the false John Paine had made this kind of dependence impossible. How could I confess my failures, my weaknesses, my inadequacies, if I needed others to believe that I had the answer to every problem? To admit I needed others would require an act of transparency, of confession. Wouldn’t it?

It was a moment triggered by the silliest thing—my inability to cover up—but it exposed a deeper, longer trend. Now I felt myself invited into something new: the admission of my need for others was necessary if I was to kill the false man. Only through this death of the false man could I plumb the depths of intimacy.

I will care for you as you learn to give in, I heard in that moment. I have you covered.

I’d learned to trust these inklings, these deeper leadings of God, and so, I stood from my chair and made my way back to my bed. I scooted my feet under the covers again and waited for something to happen. Margaret stirred, raised up on her elbow, and pulled the covers up over me. She lay back down, still sound asleep.

“Margaret?” I whispered.

No answer.

“Margaret?”

Still no answer.

“Thank you, Lord,” I prayed into the dark.

Taken from The Luckiest Man: How a Seventeen-Year Battle with ALS Led Me to Intimacy with God by John Paine Copyright © 2018 by John Paine. Used by permission of Thomas Nelson. www.thomasnelson.com.