The airplane descended toward Kigali, the capital of Rwanda, in Central Africa. My heart sank with it. I’d never felt this way before when visiting the land I’d grown to love. All the other times I’d been to Africa–so many!–I’d been filled with anticipation.

My wife, Kim, and I had worked for years as missionaries, founding and supporting a ministry to college students in the university town of Butare. We’d made close friends. The ministry had grown. We’d felt as though we were doing God’s work, as though we were exactly where he wanted us.

This visit was different. In my luggage I carried a metal plaque, which I planned to place at a roadside about halfway along the 100-mile route from Kigali to Butare. The plaque read: “On this road, on July 31, 2010, Dr. Kim Hyun Deok Foreman suffered a fatal car accident. She died in Kigali at King Faisal Hospital on August 3, 2010.”

It was summer again now, exactly a year since the accident. One year since Kim, my beloved, faithful partner for 36 years, was suddenly, horrifyingly taken from me.

What was worse was that in my mind, the accident wasn’t some random tragedy. Franc Murenzi, the Rwandan director of our ministry, had been driving Kim and me from Butare to Kigali to catch an airplane. Franc had fallen asleep at the wheel. Our car drifted in front of an onrushing bus.

Franc awoke in time to jerk the steering wheel. The car flipped, throwing Kim from a window. She was bloody and unconscious by the time I was freed from my seat belt and managed to stumble to her side. She died of massive head trauma three days later.

I never forgave Franc. Through a mutual friend, a local pastor we both knew, named Paul, I fired Franc from the ministry and told him I didn’t want him at Kim’s funeral in Kigali.

Franc came anyway, his head wrapped in a huge bandage. He gave a rambling eulogy about how the accident was just an accident, and how he’d considered Kim a second mother and was devastated. He never apologized. I sat there fuming. I’d barely spoken to him since.

The plane was over Kigali now and I could see the airport. I thought back to my first time in Rwanda, almost a decade before. Coming here had been Kim’s idea. She’d already been once before, with a group of Korean missionaries.

She’d returned home to California full of excitement about the country and the wonderful people she’d met. That was Kim. Excited about life. Eager to learn new things.

She was a university professor in San Francisco. She’d encouraged me to go into the ministry after I’d spent most of my life in the Army. We’d met while I was serving in the Peace Corps in Korea.

She was a young schoolteacher then. She helped me with my Korean. I helped her with English. We spent hours drinking tea, talking. Falling in love. We always had something to talk about. Kim never lacked for words.

But what would I say now, back in Rwanda? The problem was Franc. Amazingly, no one seemed to understand why I’d fired him. Pastor Paul even warned me at the airport after the funeral that what I’d done was causing division in the ministry.

“Some people are on your side and some are on Franc’s side,” he said. “Chris, please listen to my words. If you want to return to Rwanda and continue your work here, you must learn to forgive like a Rwandan.”

For a moment his words took me aback. It’s impossible to be in Rwanda without being reminded everywhere of the nation’s brutal genocide, those years in the mid-1990s when tribes massacred one another in escalating waves of ethnic hatred.

In the years since, the country had somehow managed to come back together. But this was different. This was a car accident, not a civil war. It was personal. Kim was my wife. The accident was someone’s fault and he’d never apologized or acknowledged his responsibility.

“When your wife is killed through someone’s negligence and he won’t say sorry, then we can talk about this,” I said to Paul. “Franc deserves to be prosecuted. I’m letting him off easy.”

Paul shook his head sadly. “Chris, my wife was killed,” he said. “During the genocide. You know that. And I have forgiven. I had to. You must too.” I loved Paul. We’d grown close working together. But I could not bring myself to follow his advice.

Back home in California, I threw myself into work. Kim and I had been building a permanent home for our ministry in Butare. The Light House would be a gathering place for Christians at the university and also a small Bible college. We’d bought land and the foundation had been laid.

Now I needed to raise funds to complete the building. I knew that that’s what Kim would have wanted.

I raised the money, even using part of Kim’s life insurance and retirement savings. But construction was complicated by the situation with Franc. People we’d worked with before didn’t want to work with me anymore.

I heard about their complaints through Paul. “They are saying, ‘How can he claim to be a pastor and treat Franc this way?’” Paul told me.

The ache I felt in my heart seemed answer enough to that question. But I began to wonder. What if Paul was right? Certainly it would make everything easier if I could just forgive Franc.

But I missed Kim so much! I kept talking to her in our empty house. I listened for her voice every morning when I awoke. I couldn’t get past the pain of her loss. How could I forgive the man who’d taken her away?

At last my doubts, and the dissension in Butare, grew too big to ignore. At a monthly breakfast I held for local Baptist pastors, I bared my feelings to my friend John, a pastor who’d held a memorial service for Kim in California.

“I’m glad you brought this up,” said John. “I’ve been wanting to say something for a long time. Chris, you are being tested. I know you loved Kim. But forgiveness is love at the testing point.

"You have to ask yourself what kind of love you have in your heart. If it’s Christian love, you’ll forgive Franc. You’ll go back to Rwanda and forgive him.”

That’s not what I wanted to hear. John’s advice was exactly the same as Paul’s. But I just couldn’t feel forgiveness toward Franc. Not through all my pain. And isn’t that what forgiveness is, a change of heart?

Yet I had to do something to make peace in Butare. For Kim. The ministry had meant so much to her. Through Paul I sent word to Franc that I would hire him again to oversee the building project. I made plans to travel to Rwanda to smooth over any remaining disagreements.

There would be no way to avoid Franc. But I would deal with that then. Maybe by that point my feelings would have changed.

The plane shuddered as the wheels hit the runway. My stomach clenched. Franc was meeting me at the airport to drive me to Butare. He would be standing there as I got off the plane. What would happen when we saw each other again?

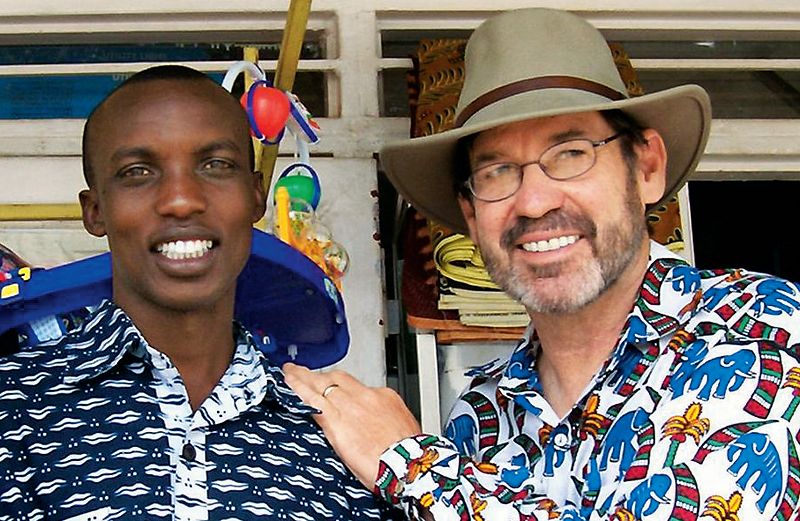

I spotted him in the throng. He saw me too. Drawing closer, I saw the terrible scar from the accident on Franc’s head. We shook hands. He asked about my flight. We walked to the car.

Conversation floated along, mostly about the project. It felt weird, as if someone was talking for me. No mention of the accident, like it never happened!

I had informed Franc about the plaque, and he’d made arrangements for us to hold a small ceremony at the site of the crash a few days later. Some people from the ministry would be there, as well as locals who’d helped at the accident scene.

We drove to Butare and checked on the building project. Franc had done a good job. The day of the ceremony we got back in the car and went to the accident site, that stretch of road I’d seen so many times in nightmares. How often had I replayed the moment in my mind?

Franc stopped the car. People were already there, gathered at the roadside. I got out. My legs felt weak. I could still see the gouges in the pavement from where the car had flipped.

I walked toward the crowd. There was the elderly man who’d used scissors to cut me free from my seat belt. There were the people who’d helped Kim into the ambulance. That’s the amazing thing about Africa, I thought. What makes it so different from America.

In Africa people don’t keep to themselves, so preoccupied with their own private goals. They live in community. They instinctively come together in crisis. They had for thousands of years.

These people had come together for Kim and me. And they’d come together in a far greater, almost unimaginable way after the genocide. Maybe some of them were from different tribes. Maybe they had relatives who’d slain one another.

I laid the plaque on the ground, then stood up to say a few words. All of a sudden the weird feeling that I’d had in the car, the feeling of someone else talking for me, evaporated. I was returned to myself, as if born again through all the pain of losing my beloved Kim.

Pastor Paul’s words seemed to ring in the air: Forgive like a Rwandan. Did I even know what those words meant?

Here I was, a Baptist pastor. A missionary. And yet these Rwandans, pierced by a national grief I could hardly fathom, were practicing Christian love just by gathering in this place today. They didn’t wait for a change of heart. They simply forgave. And the act of forgiveness changed them.

I said a few words about Kim. Then I turned to Franc. I looked in his eyes. “Brother Franc,” I said. “Forgive me for my hard heart. I know the crash was an accident and you didn’t mean to hurt Kim. I forgive you for everything.”

Franc threw his arms around me and we held each other tight. Then I hoisted his hand in the air. “This is my friend!” I cried to the crowd.

I let the words sink in as everyone around us erupted into applause. All those years ago, Kim and I had come to Rwanda as missionaries. But at that moment—no, from the very beginning—it was Rwanda ministering to me.

Download your FREE ebook, The Power of Hope: 7 Inspirational Stories of People Rediscovering Faith, Hope and Love