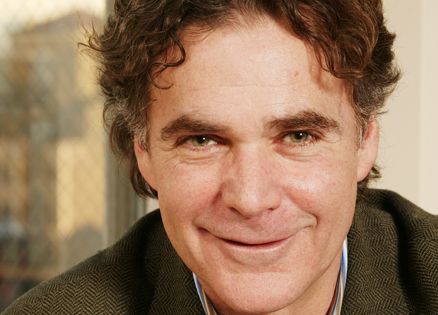

Sometimes acceptance is not so much a process but a moment. That was true for my friend and mentor, Van Varner.

Van—Uncle Van to the incredible array of people who loved him—was a wonder of a personality. There was so much of him to know. A Kentucky gentleman if ever there was one and a passionate New York transplant, he had qualities that never ceased to reveal themselves and amaze. One of the most dramatic (and indomitable) was his lifelong sense of adventure. It seemed he had been everywhere and had seen everything. No continent lacked his footprint, no sea his wake. There was rarely a place you had been that he hadn’t been before you. He was as tough as he was courtly. In his seventies he made it up to the Inca fortress city Machu Picchu, lung-bustingly high in the Peruvian Andes. I did that in my twenties—one of the few places I’d been able to boast I’d been that he hadn’t—and it was no picnic.

When he was in his sixties Van found himself in Australia, and not for the first time. But this trip he was determined to climb legendary Ayers Rock, also known by its Aboriginal name, Uluru, which means “island mountain.” Aussies usually just call it “The Rock.”

The Rock lies deep in the outback, some two hundred miles from the nearest speck of civilization, Alice Springs. Over 1,100 feet high, it is the second-largest monolith in the world and bulges like a great blister out of a vast, flat, primeval seabed, a solid mass of red sandstone two miles long and one-and-a-half miles wide. To the Aborigines Uluru is holy ground, and to anyone who has ever seen it looming from the desolate earth amid ten thousand square miles of emptiness, it can only instill a sense of awe and wonderment.

So why, at a relatively advanced age, did Van think he should climb it?

“It’s a symbol,” he said one night when we were having dinner…“Aussies take great pride in saying they climbed it,” he continued, talking through a piece of bread. “I wanted to send postcards home announcing I’d climbed it too. I wanted to accomplish it.”

Van was by no means a fitness nut. In fact, he was amused by my addiction to the gym. His principal mode of exercise was walking his dog Clay in Central Park. Still, he could be stubborn to the point of willfulness, and when he set out to accomplish something he rarely allowed anything to stand between himself and his ends.

He started out alone in the early morning, before the heat could take its toll.

“It was exhilarating,” he told me as the waiter put down our main courses. “The air was still and the silence felt almost sacred. The only sounds I heard were my feet on the rock, step after step after step.”

Soon the sun rose and so did the wind, and the way grew steeper. Now the sound Van heard was his own labored breathing. He stopped more frequently, not so much to enjoy the view but to catch his breath and mop the sweat from his brow. Others, later starters, were overtaking him. Van looked at me across the table, and shook his head, sputtering in exasperation, and then took a big sloppy gulp from his glass.

“I began to doubt that I could do it. ‘Are you a quitter?’ I actually demanded of myself out loud.” He thought about the postcards he wanted to send, how badly he wanted to boast of his climb. “Then I would set out once more, slower than before and rasping for air. My knee hurt. Everything hurt. God, it was hard!”

Three-quarters of the way up Van stopped again. This time for good. He could go no farther. His body could not keep pace with his will.

As the busboy cleared our dishes Van said very quietly, “I realized getting to the top was, for me, hopeless. I’d gone as far as I could go and I knew it.”

I couldn’t quite believe what I was hearing. Would Van go all that way just to fail? Wasn’t there going to be some miraculously supplied transfusion of strength and energy? I waited for Van’s miraculous ending to his story. But no, he didn’t get any farther toward the goal he’d dreamed of. Yet there was something else, according to Van, a sort of revelation. A strange new feeling overcame him. He gazed out at the vast, sweeping view of the outback, a view both fearsome and inspiring. This rock had been formed five hundred million years earlier, an almost incomprehensible age.

“I was suddenly quite amazed at myself,” Van said. “It was fine. I’d done my best but at my age I wasn’t going any higher. I didn’t have to. I could completely accept that. There are limits. I had found mine and it wasn’t so bad. In fact, I felt blessed because three-quarters of the way up Ayers Rock, I was seeing one of the most magnificent vistas anyplace on God’s earth, and it made me very happy.”

The bill landed on the table and Van snatched it up, holding it to his chest playfully, as if there were any chance he would actually have allowed me to pay. But I would have, gladly, for that story and to discover one of his little secrets to happiness. For Van was above all a happy—if complicated—person.

Van did send those postcards after all, proudly denoting in pen the spot three-quarters of the way up where he turned his back on Uluru’s summit, and we were all mightily impressed.

Acceptance was his success that day, and his blessing.