“Purrrrrr . . . “ the enticing sound came from a tortoiseshell cat inside a cage at the animal shelter. “Can I take her out?” I asked. “Sure,” said the attendant.

I’d loved cats ever since Grandma O’Roark had first placed a tiny kitten in my five-year-old hands. From that point on our house always had a cat curled up on the sofa or hunting stealthily in our shrubbery. A cat was one of the first essentials I got for my apartment when I came to live in New York City.

The years went by, with job following job and apartment following apartment. But there was always a cat waiting, its motor idling contentedly on purr, to greet me when I came home. That’s what had led me to this Manhattan animal shelter, and the tortoiseshell cat rubbing against the bars of the cage in front of me. I’d just lost irreplaceable Caterina, my beloved companion of 13 years, and now the idea of coming home to a catless apartment was unthinkable.

“Does she have a name?” I asked.

“The guy who dropped her off called her Onions,” the attendant said. “She’s about three years old.” I lifted her out of the cage. Dogs were barking, doors were banging. Onions dug her claws into my sweater in alarm. “It’s okay, Onions,” I said. She looked up at me with dark round eyes. Her purrs vibrated against my sweater. “You’re coming with me.”

Back at my apartment, Onions inspected my furniture and rummaged in my laundry, then climbed on top of me and we both took a nap. I woke and stroked the velvety patch of black on her head, wondering, “How could anyone have given you away?”

Figuring that Onions would like some company while I was away at work, I eventually brought home a kitten. Onions hissed a little when Lucy bounced in, but soon the three of us settled into a comfortable routine. I worried about my job and romance and money, Lucy and Onions washed each other’s face and snoozed with their feet in the air. I rushed in and out on the treadmill of a too-busy life, they yawned and looked at me like I was crazy.

One evening after an impossibly long day at the office, I fell asleep still wearing my work clothes. When I woke up the next morning, Onions and Lucy were both sitting there, gazing at me with thoughtful expressions. The bed almost rumbled with their deep, contented purrs. Peace, be still, their presence seemed to say. Calm down. Trust. Have faith. It’s all right. That was when it first occurred to me that the state of calm the cats coaxed me into was not unlike another I knew and relied on: prayer.

In the summer of 1996, when Onions was 18, her appetite waned. Then she stopped eating altogether. One morning I left her curled in a corner beside the bookshelf, and when I came home that night she was still there.

“What’s wrong, kitty?” I sat beside her and ran my fingers through her fur. Her soft purr vibrated up my arm. But she barely raised her head. This purr—intense and low—meant something different than simple contentment. Something else was happening.

The next morning I took Onions to the animal clinic. “I’m sorry,” the doctor said as he looked over the X rays. “She has cancer, and it’s spread. Operating won’t do any good at this point. All I can do is give her some medication to ease any pain she may be having.”

Over the next days Onions got weaker and weaker. I canceled all my after-work plans so I could stay by her side. I wet my fingertips with water so she could lick them, and tried to tempt her with bits of honey-baked ham, her favorite treat. She would only sniff.

Finally Onions’s breathing became so labored I wondered if she would make it through the night. Into the small hours, I lay on the floor with my hand on her side, her purrs rising and falling like an ocean swell. At some point I drifted off. When I opened my eyes, Onions was gazing directly into them.

In the morning I shook myself awake. I carried her frail body onto the terrace, thinking the breeze might soothe both of us. But she wheezed and coughed. I telephoned the vet. “If you bring her in, we may be able to keep her alive a little longer,” the doctor said.

“No, neither of us wants that,” I said. “Would you be able to…come here?”

The vet and a young assistant were at my apartment within the hour. “The shot won’t hurt at all,” the doctor said. “Onions will just drift off. Are you ready to say goodbye?”

I spread Onions’s favorite blanket across the sofa and lifted her onto it. I knelt and cradled her head in my hand.

“It’s okay, Onions,” I said. Then to my surprise I started to pray out loud. “Dear God, this cat has been a faithful and honest companion. Enfold her in your embrace and ease her way home to you.”

From within Onions’s emaciated body I felt a rumble. I put my ear against her once glossy fur. She was purring, and the sound now clearly conveyed a kind of communion, a connection with a mysterious peace that passes all understanding. Drawn into its calming energy, I continued praying. “Holy Spirit, give Onions your peace and heavenly blessings, be with all of us gathered here.”

Finally I was ready to whisper amen. Only then the thought crossed my mind: What must the veterinarian and his assistant be thinking? I looked up through wet lashes. The two of them were standing across the room with heads bowed, their lips moving silently.

Purring and praying. In times of great intensity and emotion, they blended seamlessly—and blessedly.

Some weeks later I asked a colleague from work to stay with Lucy, and went on vacation to Europe. Cats seemed to be everywhere I traveled, peering at me from the shelves of bookshops in London, from under tables in Paris cafes, from railings of bridges in Venice. In an Italian monastery gazing at a faded fresco of Jesus and his disciples, I noticed a small form in the corner of the painting. Could it be? I looked closer. A cat!

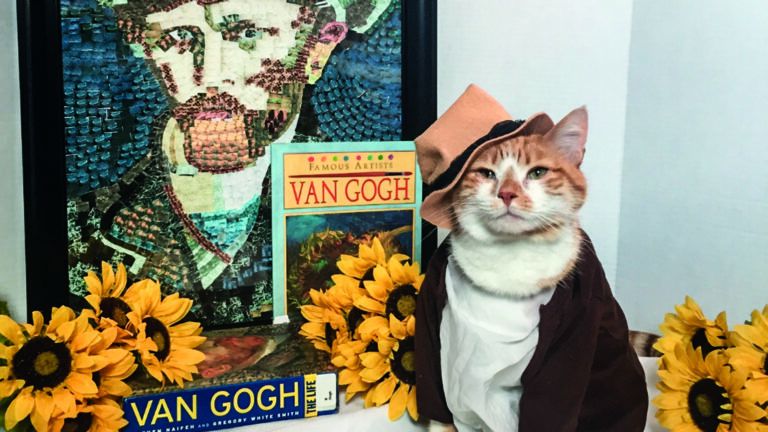

Back home I told a friend what I’d seen. “Take a look at this,” he said, giving me a copy of the book How the Irish Saved Civilization by Thomas Cahill, an account of how Irish monks, scholars and saints devoted their lives to copying religious and classical texts during the Dark Ages. I opened to the page my friend had marked and found what the author called “perhaps the clearest picture we possess of what it was like to be a scribal scholar”—an Irish poem written in the ninth century.

I and Pangur Ban my cat,

‘Tis a like task we are at:

Hunting mice is his delight,

Hunting words I sit all night.

‘Tis a merry thing to see

At our tasks how glad are we . . .

When at home we sit and find

Entertainment to our mind. . . .

So in peace our tasks we ply,

Pangur Ban my cat and I;

In our arts we find our bliss,

I have mine and he has his.

Purrs and prayers. For centuries the two had gone together.

Closing the book, I thought of a story my sister once told me, about a friend who was going through a hard time. The woman’s seven-year-old son came in and found her with her head on the table crying. “It’s okay, Mom,” the boy said, putting his arms around her. “Remember, we have cats.”