For much of my life, I have assumed that I was a spiritual failure.

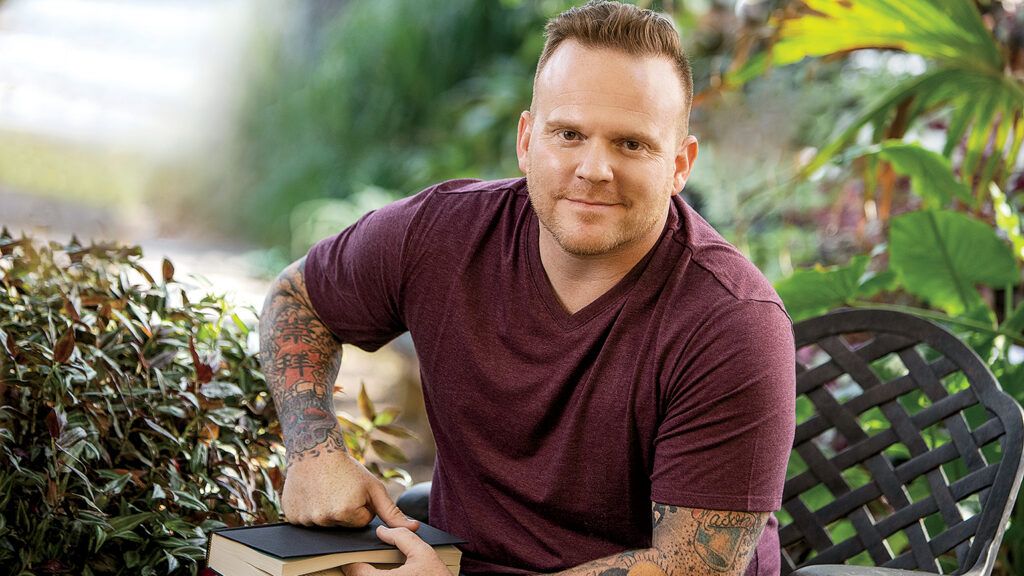

How can that be? I’m a pastor. A father. A Marine veteran.

I run a ministry that provides church services to inmates in Oklahoma prisons. I do my best to make God real to people desperate for something to believe in. How could a spiritual failure do all that?

Wind back the clock 12 years. I was transitioning to civilian life after eight years of military service, including combat duty in Afghanistan. My marriage was falling apart. I’d pretty much abandoned my faith during my time in the service. I suffered from depression. I was convinced God saw me as a worthless failure, and I agreed.

You know what pulled me out of all that? A quote I saw on Facebook. It was one of those random inspirational quotes people post. It read: “I have found (to my regret) that the degrees of shame and disgust which I actually feel at my own sins do not at all correspond to what my reason tells me about their comparative gravity.”

The language was complicated and formal, like something an Oxford don would write. I heard a simple message: Maybe my feelings of spiritual worthlessness weren’t the final word about me. Maybe I wasn’t the best judge of God’s attitude.

Maybe I had a chance after all.

The author’s name? C. S. Lewis.

Was that the same C. S. Lewis who wrote the Chronicles of Narnia books I’d read as a child? Was he a Christian? It was like he knew exactly what I felt and exactly what I needed to hear.

Who was this guy?

Answering that question changed my life. Along the way, I learned something about C. S. Lewis—a military veteran like me—that strengthened my reawakening faith.

C. S. Lewis was a best-selling Christian writer, a professor of medieval English literature at Oxford (his alma mater) and Cambridge universities and, yes, the author of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe.

More than a century after his birth, in 1898, he remains beloved by millions. I encourage readers with a military background to give him a try.

Lewis was raised in a church-going Irish family but began to question his faith during his teens. At age 19, he was sent by the British Army to the front lines of World War I and fought as an infantryman in the hideous trenches. He was wounded by shellfire and returned home a committed atheist. More than a decade passed after his military service before he rediscovered his faith.

Lewis knew the psychic wounds soldiers carry. He also knew how God can redeem all of that.

Thanks to Lewis, I now know too.

I can’t quite pinpoint the moment I lost my childhood faith. I grew up around church, but things got complicated after my parents split up and my mom joined what turned out to be a Christian cult.

My two older brothers and I went to live with my dad, who was a great man but not a churchgoer. My brothers and I attended church anyway, absorbing our congregation’s strict interpretation of Scripture that focused on God’s righteous anger toward sinners—no matter how small the sin. I was haunted by that anger, so convinced of God’s dislike for me that I turned away from faith as a teen and doubled down on bad behavior.

I enlisted in the Marines after high school and discovered a world totally alien from my Oklahoma upbringing. I met all kinds of people—other Marines, civilians in Afghanistan, military interpreters—who never gave Christianity a thought.

Did God condemn them? He probably condemned me too for my many doubts. I saw them as de facto sins.

While serving in a mortar squad, I witnessed hopelessness and despair. Where was God?

I drank to deal with my feelings and figured God hated that too. I married and had a son. Another deployment put more stress on the marriage than it could handle, and eventually my wife and I divorced. So that was it. I ended my enlistment.

I was a single father. It was just me and my son.

During my last months at a Marine base in California, my military buddies and I took turns feeding my infant son and changing his diapers, holding him in our beefy, tattooed arms. It’s a sweet image in retrospect. At the time, I felt like the worst dad ever.

I moved back to Oklahoma with my son. This might sound counterintuitive, but I sought work at a church. I barely believed in God, yet church felt safe. Maybe if I acted like a Christian, I could earn God’s approval.

I found a position leading a youth group. I was terrible at that job and, less than a year later, let go.

I tried to repair the relationship with my son’s mother. No success there either. I was just too spiritually immature.

I looked for a college. Still conflicted about God, I enrolled in a class at Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Fort Worth, using G.I. Bill money. I thought maybe I could study my way back into God’s good graces. It didn’t take long before a professor told me I shouldn’t bother thinking about ministry because of my divorce.

It was at this low point that I stumbled upon the C. S. Lewis quote on Facebook. I looked up the quote’s origin. It came from a book called Letters to Malcolm, Chiefly on Prayer. I found the book in the library and devoured it. It was as if Lewis had been living my life, feeling my feelings, asking my questions. Difficulty praying? He’d experienced it. Intense self-doubt? Same. Confusion? Check. Guilt? Check. Spiritual loneliness? Check.

I hungered for more. I read Lewis’s classic Mere Christianity, which explained the faith I had grown up with in a way that made me want to be a Christian. Until then, I thought I had to be a Christian—or else.

I read The Screwtape Letters, correspondence between two devils on how best to tempt a man of faith. How did Lewis know so much about my own temptations?

Then I got my hands on Surprised by Joy, Lewis’s spiritual autobiography. I came to the chapter called “Guns and Good Company,” about his military service. Lewis describes “the frights, the cold, the smell of [high explosives], the horribly smashed men still moving like half-crushed beetles, the sitting or standing corpses, the landscape of sheer earth without a blade of grass.”

Upon his return to England, he was determined to banish all thoughts of God from his mind.

Lewis retraces the emotional and intellectual journey that returned him to faith and a new understanding of God. Recounting the night he “gave in, and admitted that God was God,” he calls himself “the most dejected and reluctant convert in all England.”

Most dejected and reluctant convert. That was me. Why would God welcome someone who had turned his back on him in so many ways? Half a page later, Lewis answers my question: “The hardness of God is kinder than the softness of men.”

Reading those words, I broke down. Lewis experienced a God who was not the angry punisher of my childhood. Could I meet that God? Would he welcome me too?

There was no dramatic moment when I gave in and experienced God for the first time, the way Lewis did. Instead, I spent three years reading pretty much every word Lewis wrote. I enrolled as a full-time student at Southwestern and earned a master’s degree. I am finishing up a doctorate at Fuller Theological Seminary.

Student life on the G.I. Bill was great for finding my feet as a parent. Lewis was even better for building a new faith from scratch. Contrary to my professor’s warning, I did eventually find a job at a church, where members worship a loving and merciful God. I gravitated to the prison ministry because, even though I’ve never been convicted of a crime, I know exactly how those inmates feel.

They feel God could never love someone like them. They are prisoners of their doubt and shame.

One overlooked fact about military service is that it’s not just combat wounds that leave emotional and spiritual scars.

Many soldiers are like me when they enlist: young, looking for direction, inexperienced at making big life choices. They’re shipped all over the world and given enormous responsibilities. They find intense camaraderie—which vanishes as soon as they return to civilian life.

There are so many ways to mess up. So many opportunities to let someone down. It can be hard to become a mature, spiritually confident person with a healthy family life and a solid plan for the future.

If you’re like me, you can leave the service feeling like an even bigger failure than when you went in.

Reading C. S. Lewis, I realized God is okay with all of that. God knows my faults and loves me anyway. I’m a work in progress. God’s work in progress.

While still a student, I had an opportunity to enroll in a study-abroad course about C. S. Lewis hosted by Oxford and Cambridge, where Lewis had taught for more than three decades. (I’d guessed right—he was a don.) The class was held at St. Stephen’s House, an Anglican college not far from Magdalen College, Lewis’s academic home.

Soon after arriving, I learned that Lewis often walked to St. Stephen’s to say confession in the chapel.

I had to see that chapel.

During a tea break (yep, England), I slipped out of the classroom and tried to find my way to the chapel. I promptly got lost, wandering halls that might as well have been from the Middle Ages.

A student pointed me in the right direction. I walked through a heavy wooden door into a small, white-painted chapel with wood seats along the sides. Dust floated in shafts of sunlight shining through the windows. The room was silent.

I sat in one of the straight-backed seats along the wall. I pictured Lewis sitting there, getting down on his knees to ask for God’s forgiveness.

I recalled a line from a letter Lewis wrote: “I think that if God forgives us we must forgive ourselves. Otherwise it is almost like setting up ourselves as a higher tribunal than him.”

I had memorized that line because I wanted so badly to believe it. I closed my eyes. I slid off the wooden seat and got on my knees. I folded my hands.

I asked God to forgive me.

I knew in my heart that he already had.

For more inspiring stories, subscribe to Guideposts magazine.